Simulation models¶

For a more detailed representation of temperature effects and pressure losses in the district heating network, linear optimization models do not suffice. In this situation, a simulation model can be the right choice.

Scope¶

The following questions can be addressed using a simulation model:

- How do the heat losses in the network depend on the temperatures of inlet and return pipes and ambient temperature?

- How much energy is necessary for the pumps to overcome the pressure losses in the network?

- How do these properties behave if the supply temperatures change?

To answer these questions, data has to be present or assumptions have to be made about the pipe’s physical properties and the temperature drop at the consumers. Have a look at the overview table to learn about all the variables and parameters involved.

Conversely, if these are not known, running an optimization model would be the better choice. It is also possible to couple the two approaches, running an optimization first and then investigating the detailed physical behaviour. To learn about this option, please refer to the section model coupling.

Currently, the available simulation model does not handle transient states (i.e. propagation of temperature fronts through the pipes). The model evaluates a steady state of the hydraulic and thermal physical equations. This also means that consecutive time steps are modelled independently and the behaviour of thermal storages cannot be represented. A dynamic simulation model may be implemented at a later point in time.

Usage¶

To use DHNx for a simulation, you need to provide input data in a defined form. The basic

requirements are the same for all ThermalNetwork s, but some input data is specific to the

simulation.

tree

├── consumers.csv

├── pipes.csv

├── forks.csv

├── producers.csv

└── sequences

├── consumers-mass_flow.csv

├── consumers-delta_temp_drop.csv

├── environment-temp_env.csv

└── producers-temp_inlet.csv

To run a simulation, create a ThermalNetwork from the input data and simulate:

import dhnx

thermal_network = dhnx.network.ThermalNetwork('path-to-input-data')

thermal_network.simulate()

Figure 1 shows a sketch of a simple district heating network that illustrates how the variables that are determined in a simulation model run are attributed to different parts of a network. Pipes have the attributes mass flows, heat losses and pressure losses (distributed and localized). Temperatures of inlet and return flow are attributed to the different nodes. Pump power belongs to the producers which are assumed to include the pumps. Variables that describe the network as a whole are global heat losses and global pressure losses.

The above-mentioned variables can be found in the results of a simulation, which come in the following structure:

results

├── global-heat_losses.csv

├── global-pressure_losses.csv

├── nodes-temp_inlet.csv

├── nodes-temp_return.csv

├── pipes-dist_pressure_losses.csv

├── pipes-heat_losses.csv

├── pipes_loc_pressure_losses.csv

├── pipes-mass_flow.csv

└── producers-pump_power.csv

Underlying Concept¶

| Name | Math. symbol | Unit | Common values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | |||

| mass flow |  |

|

|

| mean flow velocity |  |

|

|

| pressure |  |

| |  |

Nominal pressures PN16 or PN25 |

| pressure difference |  |

| |  |

max.  |

| pump power |  |

|

|

| temperature |  |

|

Inlet pipe:  , Return pipe: , Return pipe:  |

| ambient temperature |  |

|

|

| heat flow |  |

|

|

| Water properties | |||

| density |  |

|

at at  |

| spec. heat capacity |  |

|

at at  and PN16 or PN25 and PN16 or PN25 |

| dynamic viscosity |  |

|

at at  and PN16 or PN25 and PN16 or PN25 |

| darcy friction factor |  |

– | |

| Reynolds number |  |

– | |

| Parameters | |||

| pipe’s length |  |

|

|

| pipe’s inner diameter |  |

|

Nominal diameters DN25 - DN250 |

| localized pressure loss coefficient |  |

– |  , ,  |

| standard acceleration due to gravity |  |

|

|

| altitude difference |  |

|

|

| pipe’s absolute surface roughness |  |

|

|

| heat transfer coefficient |  (sometimes (sometimes  ) ) |

|

|

| spec. heat loss per meter |  (sometimes just (sometimes just  ) ) |

|

|

| pump efficiency |  |

– |  |

| electric pump efficiency |  |

– | |

| hydraulic pump efficiency |  |

– |

The following equations are related to a single pipe.

Hydraulic equations¶

A pressure difference between two ends of a pipe occurs because of three effects:

- distributed pressure losses along the pipe’s inner surface

- local pressure losses at distinct items,

- hydrostatic pressure differences because of a difference in height.

All three effects can be captured in this formula:

Distributed pressure losses

The Darcy-Weissbach-equation describes distributed pressure losses

inside the pipe:

inside the pipe:

Together with the flow velocity

it can be written to:

where the darcy friction factor  depends on the Reynolds

number

depends on the Reynolds

number  , the pipe’s surface roughness

, the pipe’s surface roughness  and the pipe’s inner diameter

and the pipe’s inner diameter

. The Reynolds number is a dimensionless quantity characterizing fluid flows and is defined

as follows:

. The Reynolds number is a dimensionless quantity characterizing fluid flows and is defined

as follows:

is the dynamic viscosity of water.

is the dynamic viscosity of water.

In a pipe, flow is laminar if  < 2300 and turbulent if

< 2300 and turbulent if  > 4000.

In district heating pipes, flow is usually turbulent. The turbulent flow regime can be further

distinguished into smooth, intermediate and rough regime depending on the pipe’s surface roughness.

> 4000.

In district heating pipes, flow is usually turbulent. The turbulent flow regime can be further

distinguished into smooth, intermediate and rough regime depending on the pipe’s surface roughness.

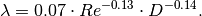

[1] provides the following approximation formula for  :

:

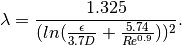

A more accurate approximation of the Colebrook-White-equation for flow in pipes is given by this formula:

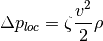

Local pressure losses

Local pressure losses are losses at junction elements, angles, valves etc. They are described by

the localized pressure loss coefficient  :

:

It is assumed that each fork has a tee installed. According to [2], localized pressure losses occur

downstream of the element that causes these losses. The values of the localized pressure loss

coefficient  were taken from [3]. In case of a tee which splits the stream,

were taken from [3]. In case of a tee which splits the stream,

is 2. In case the streams join,

is 2. In case the streams join,  is 0.75.

is 0.75.

It is also assumed that each consumer has a valve installed. Due to the complexity of determining the localized pressure loss coefficients, these losses have not been considered so far.

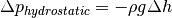

Hydrostatic pressure difference

The hydrostatic pressure difference is calculated as follows:

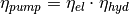

Pump power

The mass flow in the pipes is driven by the pressure difference that is generated by pumps.

The pumps have to balance the pressure losses inside the pipes. The pump power thus depends on the

pressure difference along the inlet and return along one strand of the network,  ,

the mass flow

,

the mass flow  and the pump’s efficiency

and the pump’s efficiency

.

.

In a network consisting of several strands, the strand with the largest pressure losses in inlet and return defines the pressure difference that the pumps have to generate. The underlying assumption is that the consumers at the end of all other strands adjust their valve to generate the same pressure losses such that the mass flows that are assumed are met.

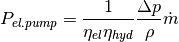

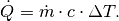

Thermal equations¶

The temperature spread between inlet and return flow defines the amount of heat that is transported with a given mass flow:

A larger temperature spread allows smaller pipe’s diameters, which reduces the investment cost of new pipes or increases the thermal power of existing pipes.

Heat losses

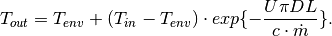

Heat losses depend on temperature level, mass flow and pipe insulation. Especially the representation of the heat losses depends a lot on the level of detail of a model. As mentioned above, in the current implementation, the thermal state of the network is assumed to be in steady state conditions. The temperature at the outlet is calculated as follows:

Where  and

and  are the temperatures at the start and end of the pipe,

are the temperatures at the start and end of the pipe,

the environmental temperature and

the environmental temperature and  the thermal transmittance.

the thermal transmittance.

In data documentation of pipes in a district heating, you often find the value of the specific heat

loss per meter ![U_{spec} [W/(K m)]](_images/math/4e462113fffed9d28b95e3a881f0e8ed8486f3d6.png) .

.

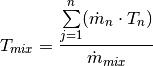

The temperature of the return flow at the fork is calculated assuming ideally mixed flows, where no

heat losses occur and the heat capacity is constant. The temperature of the mixed flow

is calculated for a number

is calculated for a number  of inlet flows, that are ideally mixed, using

the following equation:

of inlet flows, that are ideally mixed, using

the following equation:

References¶

| [1] | Chiara Bordin. Mathematical Optimization Applied to Thermal and Electrical Energy Systems. PhD thesis, Università di Bologna, 2015. |

| [2] | Donald Miller. Internal Flow Systems. 2nd ed. Cranfield, Bedford : BHRA (Information Services), 1990. |

| [3] | Beek WJ, Muttzall KM, JW van Heuven. Transport Phenomena. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons. Chichester, 1999. |